PANJA WEAVING

Are you looking for PANJA WEAVING then check out this post to know more. Panja weaving forms part of India’s glorious weaving tradition. This craft is mostly used for making durries, (light woven rugs used as a kind of floor covering). The craft gets its name from a metallic claw-like tool called panja in the local dialect, used to beat and set the threads in the warp.

The Difference between Carpet and Durrie

Although durries have a similar weaving process to carpets, they differ on various counts. A durrie is a flat, woven, light rug, usually reversible, whereas a carpet is usually heavier, with one display side. A durrie is lighter because it is mainly made of cotton, while a carpet uses wool and is thicker as well.

This also makes carpets more expensive. The process of durrie making is different from that of carpet making. Normally, the main tool in durrie making is a vertical frame composed of two horizontal beams on which the warp is fitted, unlike the big looms carpet making involves. Durrie making is also less time consuming.

Due to the difference in price, the clientele of durries and carpets differ. Durries can be found in many poor households of the country, whereas carpets normally adorn the abodes of the well-off.

HISTORY OF PANJA WEAVING

The earliest form of carpet weaving was reported in India around 500 B.C. in Buddhist texts. Also, evidence of use of carpets comes from Mongolia. These carpets were very similar to modern Persian and Anatolian carpets. Marco Polo writes of the widespread popularity of flooring’s in India in his chronicles.

However, although simple forms of flooring like namda (hand woven wool) and durrie (simple carpets woven by women in rural areas on two horizontal parallel bars) have found daily use in the villages of India for long, the carpet in its current form was imported by the Mughal emperors from Persia at the beginning of the16th century.

They not just imported carpets, but also invited and provided patronage to Persian artisans to live in India and to train Indian artisans in the art of making carpets. Soon after, Indian weavers were competing with Persians with their product in terms of quality and variety.

Although initially most of the designs and color combinations were imitated from the Persian art, very soon Indian weavers started experimenting with their own designs. Under the patronage of great Mughal emperors like Akbar and Shahjehan, Indian carpet making soon reached its zenith.

Carpets from this era later forced modern-day art connoisseurs to consider them ‘amongst the most beautiful works of art ever created’.

Carpet Production in India

Under the patronage of the Mughal emperors, carpet weaving traveled across the length and breadth of the country. Today, this craft is found in India from Jammu and Kashmir in the north to Tamil Nadu in the south and from Rajasthan in the west to Arunachal Pradesh in the east.

Some of the carpets making areas of India are:

•Jammu and Kashmir (Persian designs), Ladakh (Tibetan designs)

•Delhi (carpets as well as durries)

•Rajasthan: Jaipur, Jaisalmer, Ajmer, and Barmer

•Madhya Pradesh: Gwalior

•Uttar Pradesh: Mirzapur and Bhadohi (where 90 percent of all carpets of the country are produced)

•North-eastern states: Arunachal Pradesh, Sikkim, and Manipur (Tibetan designs)

•Andhra Pradesh: Warangal and Elluru

•Tamil Nadu, Karnataka

Regions are specially known for hand tufting in India

Although the carpet making industry is spread all across India, there are certain areas known specifically for durrie making. Some of these are:

•Haryana and Punjab Particularly Panipat in Haryana is famous for panja weaving durries

•Tamil Nadu: Salem durries in Bhavani

•Karnataka: Jamkhan durries in Navalgund

•Andhra Pradesh: Bandhaor ikatdurries in Warangal

•Rajasthan: Jaisalmer and Barmer for woollendurries

Producer Communities of panja weaving

According to Panja weavers, the relationship of the craft with caste is negligible. Though there are few individuals from the bunker caste for whom weaving is the traditional source of livelihood, caste-wise weavers are a heterogeneous group.

Many weavers are from the same region: Sultanpur, Pratapgarh, and Faizabad districts of Awadh, Uttar Pradesh (UP). This can be attributed to the fact that these districts are very close to Mirzapur and Bhadohi, the main belt of carpet production units.

Most of these weavers own agricultural land in their home villages in UP where they have to visit for long periods during the major agricultural operations of land preparation, sowing and harvesting in the cropping season.

Raw Materials of panja weaving

Both cotton and wool are used in the making of panja durries.

Cotton

The warp is invariably made of the cotton. There are different kinds of cotton thread required for the warp and the weft. Mostly both of these are procured from dealers and not produced by the weavers. The specifications for these threads are:

•For weft (or baana): 6 single cotton thread (from Rajasthan). This remains same for the two qualities of the durrie produced, regular and stone-washed.

•For warp (or taana): In this the quality of the thread used varies between the regular product and the stone-washed variety. For regular quality, the thread used is 6/6 (from Rajasthan), while for the stone-washed one, it is 12/20 (from Delhi).

Wool

Wool as weft is extensively used in making expensive durries.

There are two types of wool:

•Handspun: This is pure wool procured from the markets of Bikaner and Jodhpur in Rajasthan. This type of wool is used for durries that are colored using vegetable dyes. This wool is not of uniform gauge as it is handspun.

•Mill-spun: This, too, is pure wool, procured from Panipat and Bikaner. In durries made with this kind of wool, normally chemical dyes are used. This is cheaper than hand woven wool and is of uniform gauge.

Tools Used to make panja weaving

Taana Machine

The taana machine is made of two basic parts: a big octagonal horizontal cylinder that rotates on its axis; and a vertical frame on which a number of thread rolls can be attached.

Loom Frame

Unlike the complex looms used in weaving, this one has a vertical frame made of two beams (of wood or steel) that are horizontal. The first beam is about 2feet above the ground and the other is at about 6 feet from the ground.

The upper beam is movable and the two beams are tightened by using a screw-and-chain mechanism. The length of these beams varies depending on the dimensions of the durrie to be woven. The taana or the warp tightened on these beams has two layers that pass through a horizontal metallic frame called the reed.

The reed keeps the threads straight and equidistant from each other. Of the two layers of the taana, one remains on the outer side and the other on the inner side.

However, this position can be changed using a mechanism called the kamana(a v-shaped wooden frame where the ends are bound with a tight piece of rope) and ruchh (two bamboo pieces on which the kamana in attached with the beam, just above the reed).

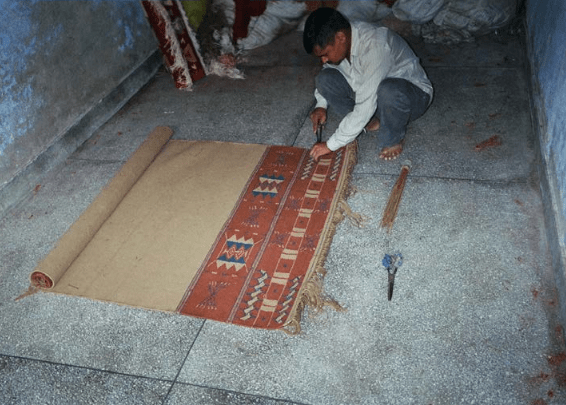

Panja

Panja is a metallic, claw-like fork used for beating the weft threads in the warp so as to adjust it there. The beating is directly proportional to the stability of the durrie.

Charkha

A charkha is used for making rolls or bundles of yarn for the weft

Scissors

A pair of scissors is used to provide the finishing touch to the durrie by cutting protruding knots, weft threads, etc.

The Process of Panja Weaving

The process of panja weaving has the following steps:

Designing

The designs are either provided by the agencies placing the order with the weavers, or are supplied by the weavers themselves based on traditional designs found in the region. They may also be inspired by designs published in various books or magazines, or from an existing product.

Raw Material

Raw material for the process (cotton for the warp, and cotton and wool for weft) is readily available with local dealers. It has to be processed further in order to make it suitable for using in the process of weaving. These processes are discussed in detail later.

Dyeing

Dyeing is an important part of the process of durrie making. It may be done both on a smaller scale (where the artisans dye the yarn in their small tubs) or in dyeing factories (where the process is more or less automated).

Two types of dyes are used in this process: vegetable dyes (which use indigo, harad, mangeetha, pomegranate peel, etc.) and chemical dyes (normally fast dyes are used). Yarn dyed with these two types may be differentiated by the uniformity of color.

While a yarn bundle dyed with chemical dye is uniformly colored, a bundle dyed with the vegetable dye has varying shades.

Yarn Opening for Weft

After the dyeing process, the yarn is normally received by the weavers either in the form of bundles or rolls (the latter in case of dyeing factories).

In case of bundles, the thread needs to be freed from tangles and stretched in order to make them tighter. For this, it is taken through a process of reeling using a charkha. This process is mainly done by women.

Warping

The master weaver carries out the process of warp making depending upon the requirement of the design and color combination.

He uses the taana (warp) machine for this. The thread rolls are put on the vertical frame in the desired color combination. This is a movable frame. The ends of the thread are taken from the rolls, passed through another, smaller, grid-like frame that guides the thread, and are wound on the octagonal cylinder in a combination that the master weaver decides for making the taana roll.

This process starts from one end of the cylinder and goes on till the entire cylinder is covered with thread. Once this is achieved, the log upon which the taana is wound is fitted into the blocks between the cylinder and the frame. The tightly wound thread on this log is then provided to the weaver who uses it on the loom frame.

Weaving

For weaving, the warp is bound on the two beams of the loom (the warp roll forms the upper beam and it is wound on the lower beam). The warp has two layers, which pass through a flat metallic reed that guides the threads by keeping them equidistant from each other. On the bench provided just in front of the loom, facing the warp, one or two weavers sit, depending upon the width of the durrie.

If the width of the durrie is more than five feet, it will occupy the whole beam and in this case only one weaver can work on the loom. If its width is less than three feet then in that case two weavers can work at the same time on two different carpets of less width (three feet each) on the same beam and same loom frame.

The weavers keep the design in front of them (either in the form of a graph or a sample) while weaving the first few articles of that design. After awhile, when they have memorized the pattern, the work becomes faster. They pull a fixed number of warp threads, depending on the design, towards themselves and take the small bundle of weft across the warp threads to fill the gap longitudinally. To facilitate the design, the warp is marked at regular intervals to guide the weaver about the location of a particular feature (like a flower) in the design.

Once one row of weft is completed, the weavers beat it to settle it tightly into the warp by using the panja. It has five metallic fingers bent like a claw. These fingers move between the warp threads similar to a comb in hair.

Once the weft threads are tightly beaten between the warp with a panja, the weaver exchanges the upper and the lower layers of the warp by using the kamana and rucch. This locks the weft between the two layers of warp, providing more strength and durability to the durrie.

The weavers keep tightening the warp by adjusting the two beams with tightening screws. This makes the durrie crisp and strong and its designs symmetrical. They go up the warp as they fill the lower part of the warp.

Finishing of panja weaving

Once the durrie is completed, the weaver takes it off from the loom and hands it over to the master weaver for proper finishing.

In case of a stone-washed durrie, the master weaver sends it to the washer man who washes it using water, detergents and potassium permanganate.

The master weaver then knots the loose ends of the durrie and also rectifies any problems that it might have developed during the weaving. For example, the durrie may develop differential width at the fringes due to shrinkage. If so, It is set it tightly on a frame and kept there for a day or two so that it is stretched properly.

The master weaver then sends it to the clipper, who clips off all protruding threads and knots using a pair of scissors, giving the durrie a smooth look.

Use of the Product (panja weaving)

Durries woven in the panja method are used in a variety of ways. Since these durries come in various dimensions, they are used as flooring, sitting mat sand even upholstery (in the case of ethnic designs like naga).