Although Orissa is traditionally not a cotton growing state, it has a substantial and numerically large weaving population that depends on the handloom industry for its livelihood. Weaving is traditionally a caste based occupation. During monarchical rule, the handloom industry and the different weaving sub-castes with their specialties in specific designs and fabrics flourished in different parts of Orissa under the local royal patronage. Since medieval days, the handloom industry has gained the status of the largest craft industry in Orissa. In the post independence era also, its importance in the economic life of Orissa cannot be ignored.

Craft tradition

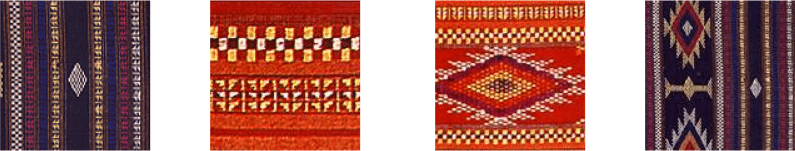

As mentioned earlier the skill of the weavers of Orissa varies widely across different weaving sub-castes, as do the types and quality of the fabrics woven by them. Handloom weavers of Orissa produce a wide variety of textiles such as saris (which contribute the major component), dress material, scarves, dhotis, towels, other fabrics of day to day use as well as the highly artistic calligraphy on fabrics (wall hangings), etc. There is a great range in design and technique, and different areas have come to be known for particular specialties. There is the double ikat with highly intricate designs woven by the Bhulia weavers of undivided Sambhalpur, Bolangir, Kalahandi and Phulbani districts (such as Pasapalli, Bichitrapuri, etc.); the single ikat woven in Maniabandha, Nuapatna area of Cuttack district (Khandua designs); extra warp and weft designs like Bomkai; silk of Berhampur; cotton of Khurda district; vegetable dyed fabrics of Kotpad (Koraput district); fine count saris of Jagatsinghpur and Tassar fabrics of Gopalpur, Fakirpur in Kendujhar district. The richness and wide diversity of Orissa handloom has yet to be exploited to its full potential.

Ikat

Known throughout the world as ikat, derived from the Malay word mengikat meaning to tie or bind, this is a complex and meticulous process. Before the cloth is woven, the warp or weft threads (single ikat), or both (double ikat), are bundled and bound with threads or rubber bands that resist the action of dye stuffs. They are then repeatedly dyed to create bands of pattern. The weaving process itself is relatively simple.

In India ikat is woven in Gujarat, Andhra Pradesh and Orissa. It has some distinct varieties, known by the specific and regional titles of ‘patola’, ‘mashru’ and ‘telia rumal’. In Orissa, ikat is popularly known as ‘bandha’ or Sambhalpuri weave.The oldest tradition of ikat weaving is probably that of Gujarat state.

Three basic forms of ikat

• Single ikat: where either warp or weft yarns are tied and dyed.

• Combined ikat: where warp and weft ikat may coexist in different parts of the fabric.

• Double ikat: where both warp and weft threads are tied with such precision that when woven, threads from both axes mesh exactly at certain points to form a complete motif or pattern.

Ikat in Orissa

Whereas northern India has historically been the scene of repeated invasions and hence susceptible to external influence, Orissa enjoyed greater immunity, being isolated from the rest of India by ranges of hills on the west and the Bay of Bengal to the east. Consequently the ‘bandha’ textiles of this region have a distinct native identity. In contrast to the imposing, mosaic-like appearance of the patola from Gujarat, traditional single ikat bandhas from Orissa had a soft curvilinear quality. The charm of these cotton and silk ikat textiles lies in the rich texture. The ’feathered’, flame-like, hazy effect of the forms, is a great contrast to the sharp, grid based patterns of the patola. Also, the effect achieved by the addition of extra weft threads woven beside the ikat areas, gives the band has a unique appearance.

Patronized for generations by the local population of all social strata, the bandha industry of Orissa is represented almost entirely by the two weaver communities -the Mehers of Sonepur and Bargarh and the Patras from Nuapatna and Cuttack regions. Each group developed its own characteristic styles. Presently there are approximately 40,000 looms scattered in and around villages of Attabira, Bargarh, Barpalli, Sonepur in the west and Nuapatna in the east.

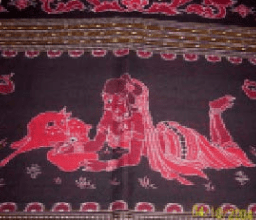

Orissa also produces large quantities of ikats in tasar silk. Certain ikat textiles woven in silk are used for religious purposes in the famous temples of Jagannath Puri. In Nuapatna, one of the oldest weaving centers, there exists an intriguing tradition known as ‘pheta’, of weaving slokas or verses from the Gita Gobinda texts into the fabric.

The earliest documented evidence was found by Sri Sadashiv Rath Sharma, a scholar and devotee, in the daily diary (Madala Panji) of King Ramchandradev II who ruled in Puri (circa:1719 A.D). The essence of the inscription is as follows, “Jaydev, the great poet of the 12th century used to offer the sacred ‘Gita Gobinda’ text to Lord Jagannath, Lord of the universe. In order to ensure close proximity to his deity, he decided to procure fabrics with lyric woven into them, with which to adorn the image. So impressed was King Ramchandradeva by this symbolic act that he immediately placed orders for these fabrics in Nuapatna.” Each pheta contained one sloka or verse woven into it. Today the weavers from the Patra community in Nuapatna continue to weave these traditional Gita Gobinda fabrics.

Another interesting custom, which throws some light on the antiquity of ikat weaving in Orissa is found in a tradition practiced by some Patra weavers of Nuapatna. Each family preserves a small piece of fabric woven by their forefathers to the seventh generation. When an elder dies, his successor adds his fabric to those of his ancestors. The fabric, apparently endowed with some mystical significance, is kept in a secret place and is not ordinarily available for inspection. According to Jagannath Kethial who chanced to see a set, each one of them was woven in the ikat technique.

Whereas traditionally Patra weavers from Nuapatna specialized in bandhas on tussar silk and the Mehers of Bargarh wove mainly cotton ikats, today the band has of Orissa are poised at the crossroads of change. Rigid distinction no longer exists as divisions of skill and specialization have entered ikat production in many villages. Some specialize in tying and dyeing, while neighboring villages buy the dyed yarn to be woven into saris. In the realm of design, traditional motifs, once confined to one or other weaver group, are now borrowed and redesigned by both communities. Weavers who once wove only saris for local usage, now produce yard age, scarves, linen, etc., for urban and export markets.

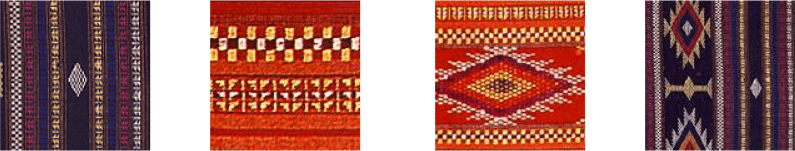

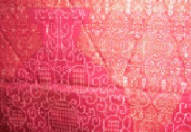

Ikat itself has many styles among the weavers of Orissa. The district of Sambalpur lends its name to the Sambalpuri weave. The Sambalpur Vichitrapuri sari has an extra warp pattern on the body and an extra weft pattern on thepallu, while the shakarapara designs of squares of different colours: white, red and black are in double ikat. The colour scheme for the weave is predetermined with extraordinary precision, so that when the dyed threads are woven together, the design appears in the finished textile, as if by magic.

Bomkai Weave

The village of Bomkai in the Chikiti tehsilin the Ganjam District, near the Andhra border lends its name to the bomkaisari. The Vaishnava Chikiti ruler patronized, along with theatrical dance and stilt opera, the bomkai sari. The bomkai represents one of the weaving traditions of Orissa that combine different techniques.

Legend has two possible theories about the origin of the bomkai sari. The early rulers had apparently founded many villages, Bomkai being one among these. The diwan (ruler) of Bomkai was a descendant of merchants (from Mantrindi) who had acquired wealth through trade with Southeast Asia, and had become influential men in Orissa where they settled.

They were given estates by Orissa rulers, Bomkai being one of them. Bomkai had a few weavers at this time: there is debate about whether the tradition of the bomkai sari existed in the village (and in Chikita Raj) before the settlers from Mantrindi came, or whether these settlers brought the tradition with them.

Created with the three shuttle weaving technique and the extra healed shaft design on primitive pit looms, it is a labor intensive product, and hence expensive. Bomkai saris combine bandha and supplementary threadwork. This is called kapta jala, which refers to the dobby mechanism (jala). The bomkai sari was traditionally worn by high-caste Brahmins during rituals and ceremonies. Certain saris have specific religious purposes: ‘the white badasaara sari is used by the Soura and Kandha tribes to wrap the statues of their deities whereas thekala badasaarais draped behind the image of the goddess Thakurani’. Quotation marks should be used only if the source is being mentioned.

Field: The bomkai saris are created in coarse low-count cotton but are always brightly dyed (often black, red, or white grounds). The body of the sari is ‘accented with a single buttahor motif of a bird on a tree’. Again quotation marks only if source mentioned. (Henceforth I will remove all such quotation marks.)

Borders: Supplementary weft and warp borders. For the border, popular motifs are dalimba or pomegranate corns and saara or seeds topped with a row of kumbha or temple spires. Both the dalimba and the saara are diamond shaped beads where the former has a dot within and the saara is halved vertically.

End-piece: Supplementary weft and warp end-pieces. A broad band of supplementary warp patterning, creating a latticework of small diamond shapes is the usual design. The field’s warp threads are cut and re-tied to different coloured warps for the end-piece, thus creating an unusually dense layer of colour for the (fairly large) end-piece.

This is known as muha-johraor ‘end-piece with joined threads’ (muha= face; johra = join). To achieve a solid colour effect in the pallu, two different coloured warp threads are twisted with starch and joined at the junction where the palluand body meets. (a muha-johra bada-saarais a sari that is ‘blood red in colour and has dotted diamonds [saara] in the border.’)

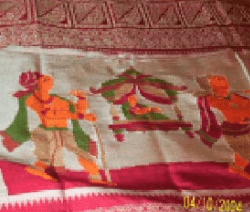

In the bomkai sari, on a bright background, the weavers create panels of contrasting motifs in the anchal or pallu. The motifs are many: karela or bitter gourd, the atasi flower, the kanthi phul or small flower, macchi or fly, rui macchi or carp-fish, koincha or tortoise, padma or lotus, mayura or peacock, and charai or bird being some of the more common ones. Motifs are freely composed. Unlike other traditional saris, the pallav pattern does not have any regular grading of motifs, like for example, heavy to light. As only the rich Brahmins wore this sari each piece was different, thus making each creation an exclusive one.

Traditionally, vegetable dyes were used: myrobalan for black, turmeric for yellow, lac for dark red/ maroon, girmati or ochre treated with ghee for light red, and acacia skin for chrome orange. However, in the past few decades, weavers buy dyed yarn, which is commonly chemical dyed.

Type of looms

1. Pit loom

2. Frame-cum-semi pit loom

3. Advanced loom

4. Power loom

The throw shuttle frame loom is ideal for the intricate designs created by the Bomkai and ikat weaving processes. The quantity of yarn taken for weaving depends on the design, the reed and pick of the product, the denier of the yarn required, the denier of the yarn required as extra warp and extra weft.

Raw materials

Cotton

Type of yarn: 2/100s count mercerized cotton for warp and weft

Silk

Type: Mulberry and non-mulberry (tussar, muga, eri) Source: Mulberry -Malda and Murshidabad in West Bengal; Bangalore; and majority of silk from Sidlighata in Mysore

Non-mulberry – Tussar – OrissaEri – Orissa and North East

Muga- North East

Type of yarn: 20-22 denier of 3 ply as warp and 18-20 denier of 4 ply as weft.

(The thickness or the yarn count of silk threads is based on a system of weight known as denier. A denier represents a weight of 0.05 gram and the standard length of a raw silk skein is 450 meters. An increase in weight of a standard length indicates an increase in diameter and, therefore, denier)

Processes at the Resource Centre In Angul

Degumming of silk yarn

The silk yarn purchased still contains some sericin or silk gum that must be removed in a soap bath to bring out the natural luster and the soft feel of the silk. For this purpose ‘Sunlite’ soap cake is used. As much as 20-25% of the gum gets removed from the silk. When the gum has been removed, the silk fiber or fabric is a creamy white colour, beautifully lustrous, and luxuriantly soft.

Degumming takes place in order to prepare the silk yarn for dyeing. A small amount of sericin is sometimes left in the yarn or in the fabric to give the finished product added strength or a dull finish. Ata time, yarn required for two saris is taken for degumming.

Dyeing of the yarn

The processed yarn is tied to a wooden frame and tied as per design, such that each bundle has 25 threads. The dying process is carried out on a small scale. The majority of the dyes used here are chemical (azoic) dyes. The process of dyeing is the same for all dye(Should this be yarn and not dye types) types. Water is prepared in such a way that there is certain softness present in it. All colour shades have different temperatures and recipes for their preparation. Acetic acid is added to the mixture in the end. The wooden frame with the threads tied is immersed into the prepared solution for dyeing the yarn. Some of the vegetable dyes used are catechu, onion, anaras and basant flower.

After degumming and dyeing of the yarn; the threads are dried in rooms or in the open.

Once dry, the yarn is spun on a spindle and gathered onto a bobbin or konda. The local name for it is osari. Each bobbin weighs 120 grams.

The thread from the bobbin is rolled out onto the drum. At one time, thread from 120 such bobbins is wrapped around the drum.

From the drum, threads are separated and passed through reeds (comb like structures), such that 2 threads pass between a reed eye (space between 2 reeds). The threads further pass through a reed buoy.

The yarn is finally rolled out onto a rod and taken outside where it is checked for knots.

The process of rolling done here is known in the local language as thaani. The threads are rolled onto a wooden log known locally as thun. On completion of the process of checking for knots this thun is taken with the rolled thread on it and placed behind the loom set for weaving.

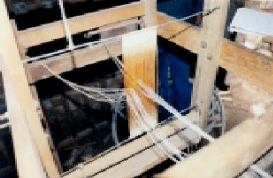

Preparation for weaving

In the weaving operation, lengthwise yarns, which run from the back to the front of the loom, form the basic structure of the fabric and are called the warp. The crosswise yarns are the filling, also known as weft. Before weaving, these warp and weft threads are spun and dyed in the desired size and design.

Toward the front of the loom, a number of shafts are positioned across its width. These are attached to the treadles, and by moving them the weaver lowers the shafts. Straps connecting the shafts are passed over a beam and back to an alternate shaft to stabilize them. Each shaft consists of a large number of vertical loops of thread (known as heddles) through which an individual warp thread has to be passed, one thread per loop. The craftsman who makes the shafts is often responsible for threading the warp through them, and then, in groups of two, through spaces in the comb-like reed. The reed has a sturdy frame of iron. Once threaded through the shafts and the reed, the warp is secured to a beam immediately in front of the weaver. Two shafts are needed to weave a plain weave fabric: as a treadle beneath the loom pulls down one harness, the other harness rises, to create a wide shed through which the weaver pass the shuttle containing the weft. By pressing the other treadle, the alternate threads are raised, and by returning the weft to where it started, it interlaces with the warp to form a stable fabric.

To make a sari with a reed count of 6800 it can take up to one and a half months of working days. The typical sari is 47 inches long and weighs around 500 grams. However the percentage of wastage is only 5%.

Pricing

Weight of the silk before degumming = Weight of the sari -Weight of the Art Silk+ the loss of the silk during Weaving.

Material:

Weight of the Silk before degumming = art silk/ silk x 4/3(75%)

Weight of the silk = 1/3 of the warp2/3 of the weft

+Raw-Material

+ Conversion charges

+ Degumming charges

+ Dyeing charges

+ Design cost

Add: Labour charges

Packing charges

Transportation charges:

Total cost:

Add Profit:

Selling price of the sari

Changes in the recent years

Technology

Though weaving on pit looms is far more time consuming, the weaving comes out far neater on a pit loom compared to

jacquard.

Design

Patterns: Apart from the traditional single, small motifs consisting of fishes, conches etc. the resource center has come a long way in designing pencil-drawing type motifs. These figures cover the entire length of the pallu. The motifs are inspired from mythological characters. A combination of both ikat and bomkai weaves can be found on one sari.

Fabric Engineering: After a lot of research and hard work has developed spun tussar, one of its kind, which is 100% silk but feels soft like cotton. Earlier, this type of cloth consisted of equal quantities of both cotton and tussar silk.

Product Diversification: Apart from the weaving for saris and cloth for religious purposes, these days cloth is woven for stoles, shawls, dress material, mats, ties, mufflers and furnishings.